'Squid pops' monitor sea meals

Researchers are using ‘fish lollies’ to capture predator activity.

Researchers are using ‘fish lollies’ to capture predator activity.

An international team of scientists, including three UNSW researchers, has sketched the first global “BiteMap”, showing where the ocean’s mid-sized predators are most active.

They produced the map by fishing with dried squid baits called “squid pops”.

The team discovered rising temperatures can shape entire communities of predators, with potential impacts lower down the food web.

The new study has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

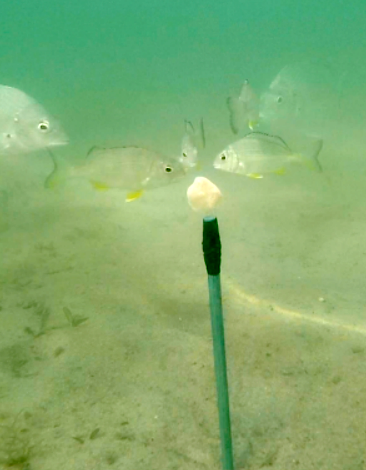

A “squid pop” consists of a piece of dried squid meat attached to a stick.

“Most people think they’re lollipops, and I guess they could be for fish,” said co-author Jonathan Lefcheck.

Researcher Emmett Duffy invented the squid pops a few years ago while searching for a standardised way for researchers anywhere in the world to measure fish feeding and compare results.

“We basically looked at every kind of bait you can possibly buy in a tackle shop....In the end we settled on this dried squid, and that’s kind of the gold standard,” he said.

Fish and crabs generally liked eating the squid in tests, and it is easy for scientists to buy and store it in dried form.

“I will say it stinks,” Dr Duffy said.

The team planted the squid pops at 42 underwater sites spanning five continents.

They ranged from the southern tip of Australia to northern Norway just inside the Arctic Circle.

Capturing the north-south range enabled the biologists to cover most of the global range in sea temperature. This, in turn, allowed them to explore how climate change could shape marine food webs in the future.

They also surveyed the types of fish and crabs present, using seine nets at 30 of the sites and video cameras at 14 of them.

The team’s results were surprising.

“We normally expect predation to be most intense in the tropics, where temperatures are hottest, but this study had the surprising result that predation peaked in subtropical regions like NSW, where our team observed very high rates of predation,” said UNSW researcher Professor Alistair Poore.

Although the squid pops disappeared faster in warm water, temperature also influenced the types of predators present at each site.

Fish like porgies, half-beaks and grunts were among the most common animals caught on camera snacking on the squid pops.

These fish were all but absent when scientists surveyed the hottest sites near the equator. In other words, warm waters not only increased appetites, but altered biodiversity.

In fact, statistical analysis showed that temperature had a stronger influence on which animals were present at each site than on how much they were eating.

While warmer temperatures generally increase animal activities like eating, researchers are only just starting to grasp what those changes mean for marine ecosystems as a whole.

“While we have been able to use satellites and oceanographic buoys to understand how things like temperature or nutrients vary around the world, it is just as important to measure how species interact,” said A/Prof Verges.

“We know predation can be an incredibly important force shaping ecological communities – it can determine what species are present in a certain ecosystem. For example, where there are a lot of top predators, we get healthier kelp forests, because the predators eat the sea urchins that would otherwise overgraze the kelp.

“The results from this study suggest that as the oceans continue to warm we may see increases in predation at the highest latitudes, for example around southern NSW, Victoria and Tasmania.”

Print

Print