Carbon-hungry bug discovered

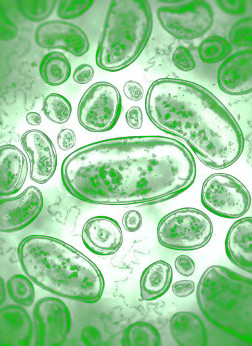

Scientists have discovered a microscopic ocean predator that appears to have a taste for carbon capture.

Scientists have discovered a microscopic ocean predator that appears to have a taste for carbon capture.

A single-celled marine microbe could become a new weapon in the battle against climate change.

Experts at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) discovered the species, and found that it has the potential to sequester carbon naturally, even as oceans warm and become more acidic.

The microbe, abundant around the world, photosynthesises and releases a carbon-rich exopolymer that attracts and immobilises other microbes. It then eats some of the entrapped prey before abandoning its exopolymer “mucosphere”.

Having trapped other microbes, the exopolymer is made heavier and sinks, forming part of the ocean’s natural biological carbon pump.

This behaviour has never been observed before, according to marine biologist Dr Michaela Larsson.

Marine microbes govern oceanic biogeochemistry through a range of processes including the vertical export and sequestration of carbon, which ultimately modulates global climate.

Dr Larsson says that while the contribution of phytoplankton to the carbon pump is well established, the roles of other microbes are far less understood and rarely quantified. She says this is especially true for mixotrophic protists, which can simultaneously photosynthesise, and consume other organisms.

“Most terrestrial plants use nutrients from the soil to grow, but some, like the Venus flytrap, gain additional nutrients by catching and consuming insects. Similarly, marine microbes that photosynthesise, known as phytoplankton, use nutrients dissolved in the surrounding seawater to grow,” Dr Larsson says.

“However, our study organism, Prorocentrum cf. balticum, is a mixotroph, so is also able to eat other microbes for a concentrated hit of nutrients, like taking a multivitamin. Having the capacity to acquire nutrients in different ways means this microbe can occupy parts of the ocean devoid of dissolved nutrients and therefore unsuitable for most phytoplankton.”

The researchers estimate that this species, isolated from waters offshore from Sydney, has the potential to sink 0.02-0.15 gigatons of carbon annually.

“This is an entirely new species, never before described in this amount of detail,” says Professor Martina Doblin, senior author of the study.

“The implication is that there’s potentially more carbon sinking in the ocean than we currently think, and that there is perhaps greater potential for the ocean to capture more carbon naturally through this process, in places that weren’t thought to be potential carbon sequestration locations.”

The experts are now wondering whether this process could form part of a nature-based solution to enhance carbon capture in the ocean.

“The natural production of extra-cellular carbon-rich polymers by ocean microbes under nutrient-deficient conditions, which we’ll see under global warming, suggest these microbes could help maintain the biological carbon pump in the future ocean,” Prof Doblin says.

“The next step before assessing the feasibility of large-scale cultivation is to gauge the proportion of the carbon-rich exopolymers resistant to bacteria breakdown and determine the sinking velocity of discarded mucospheres.

“This could be a game changer in the way we think about carbon and the way it moves in the marine environment.”

The full study is accessible here.

Print

Print