CCS checked for QLD

A new study suggests carbon capture and storage (CCS) could be a real option for Queensland.

A new study suggests carbon capture and storage (CCS) could be a real option for Queensland.

While CCS technologies have been criticised for their alleged ineffectiveness, high cost and ability to perpetuate otherwise highly-destructive industries, the Australian Government recently flagged a role for such measures in its carbon emissions roadmap.

The study by the University of Queensland looked at the establishment of a large-scale CCS hub in southern Queensland, and has unearthed real promise for CCS as a way of significantly reducing carbon emissions over the next 40 years or more.

Researchers found an annual 13 million tonne emission cut, or the equivalent of taking 2.8 million cars off the road each year, might be achieved by retrofitting the most modern existing ‘baseload’ power plants.

Director of the research project, UQ Professor Andrew Garnett, said the scheme would need to commence almost immediately, but it could be made with a number of incremental investments to avoid a large ‘all or nothing’ approach.

“Carbon capture and storage may be essential to buy us the significant amount of time required to develop reliable, affordable, low-carbon, baseload power and other decarbonisation technologies,” Professor Garnett said.

“This would allow us to continue to provide energy, while creating new employment and prolonging existing jobs in regional communities.”

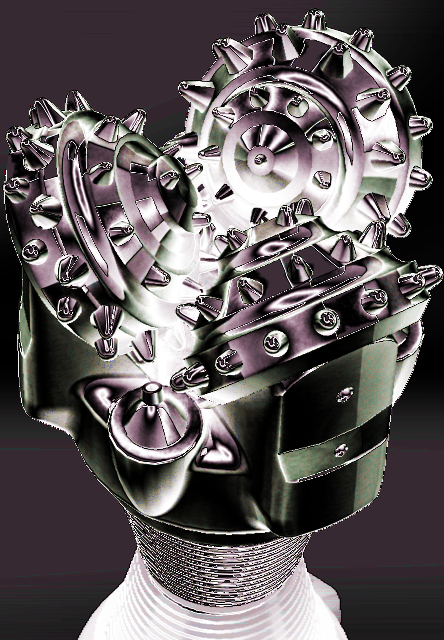

CCS involves capturing carbon from power stations, transporting it by pipeline and burying it more than 2.3 kilometres underground.

The world’s peak energy body, the International Energy Agency, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change believes that CCS technology is a potential tool to ensure global emission reductions are met over the next several decades.

“We are seeing an inexorable growth in global population and increased demand for food, water and energy, leading to greater urbanisation and spiralling emissions, yet new energy technologies such as renewables, grid scale batteries or hydrogen are not yet ready to replace coal and gas in power generation,” Professor Garnett explains.

“Realistically, development of renewables at the scale needed to replace coal and gas in power generation is many decades away. To keep the lights on while driving emissions down during this transition will take a complex, dynamic and changing energy mix over the next 40 plus years.

“There is no single, magic bullet for decarbonising the electricity supply - we will need renewables and energy storage and a clever mix of existing energies to reduce the carbon intensity of baseload.

“Therefore, the option of carbon capture and storage should be seen as a critically important and material opportunity to make an orderly transition to a low-emission power generation mix.”

The study found deep emission cuts might be achieved by establishing a large-scale CCS ‘Hub’ scheme built around, for example but not limited to, retrofitting existing modern, supercritical coal power plants in Queensland, including Millmerran, Kogan Creek and possibly Tarong North.

These are in close proximity to the areas notionally identified for their storage potential in the deepest part of the Surat Basin.

Professor Garnett said the sooner that CCS was realised in the lifespan of these power stations – currently about 35 years – the greater the impact of the initiative.

He estimates three to four years might be required to confirm the option as feasible, then another few years to set up the commercial venture and finalise engineering.

This could be followed by a phased, sequential build-out in several stages over several years, maintaining a steady, regional employment stream while significantly cutting emissions.

“The next steps would be to gather more field data, consult with communities, carry out regulator investigations and conduct a full feasibility study,” he said.

“It’s conceivable that commercial scale – meaning of a scale which creates deep emissions cuts - capture and storage could commence around 2030, but we’d need to start the process now.”

Print

Print