Fossil adds to life story

A new fossil discovery shines light on Earth’s evolutionary history.

A new fossil discovery shines light on Earth’s evolutionary history.

Researchers at Flinders University, in collaboration with international experts, have discovered a remarkably well-preserved Devonian coelacanth fossil in Western Australia.

This finding offers fresh insights into the role of plate tectonics in evolutionary processes.

The study, published in Nature Communications, links tectonic activity to species evolution, particularly during periods of Earth's shifting crust.

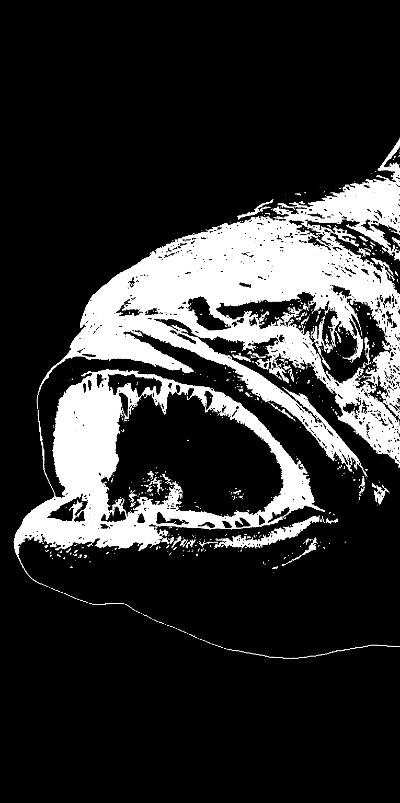

The fossil, Ngamugawi wirngarri, was found in the Gogo Formation, an ancient tropical reef now a dry, rocky expanse.

It dates back approximately 380 million years and belongs to a group of fish thought to have been extinct, until a live coelacanth was caught off the coast of South Africa in 1938.

The Ngamugawi wirngarri fossil is significant for its preservation, capturing a critical moment in coelacanth evolution.

This period saw the transition from more primitive forms to anatomically modern coelacanths, providing scientists with a unique opportunity to examine the early anatomy of this species.

According to Dr Alice Clement, lead author of the study, the fossil demonstrates how “tectonic plate activity had a profound influence on rates of coelacanth evolution”.

Clement explains that tectonic shifts likely created new habitats, leading to the emergence of new species, a phenomenon mirrored across evolutionary history.

“New species of coelacanth were more likely to evolve during periods of heightened tectonic activity,” she said.

The discovery confirms that the Gogo Formation remains one of the most abundant fossil sites globally, preserving not only coelacanths but also other species that thrived during the Late Devonian period.

Professor John Long, co-author of the study, said the fossil provides invaluable clues about early vertebrate evolution, noting that “many parts of human anatomy originated in the Early Palaeozoic”.

Coelacanths have long intrigued scientists.

With robust, lobe-shaped fins, they are more closely related to tetrapods, the first vertebrates to walk on land, than to modern fish.

Their evolutionary history spans over 410 million years, and they were once thought to have vanished during the mass extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs.

However, their ‘Lazarus species’ status was established with the surprising 1938 discovery of a living coelacanth.

Professor Richard Cloutier, another co-author of the study, suggests that coelacanths should no longer be considered “living fossils”, as they continue to evolve, albeit slowly.

The team’s analysis showed that, although coelacanth evolution slowed after the dinosaurs' extinction, subtle changes in shape and genome have continued.

This discovery provides another piece to the puzzle of vertebrate evolution and highlights the importance of plate tectonics in shaping life on Earth.

“This is a groundbreaking step in understanding how tectonic shifts have driven the evolution of species over millions of years,” Dr Clement said.

Print

Print