Locals open world of MOFs

An international team featuring local expertise has plumbed the possibilities of advanced nano-materials.

An international team featuring local expertise has plumbed the possibilities of advanced nano-materials.

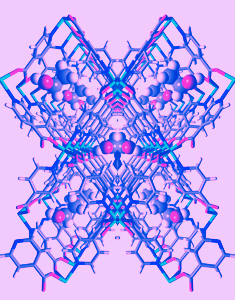

The scientists say they have found a way to harness the potential of designer crystals known as Metallic Organic Frameworks (MOFs) - the most porous materials on the planet.

MOFs are run-through with microscopic holes, so much so that a single teaspoon of the powdery material has the same surface area as a football field.

Since their discovery in 1999, they have been used in an array of fields including pharmaceutics, electronics and horticulture.

Although the novel materials have a powerful appeal for scientists, one of the roadblocks to realising the full potential of MOFs is their erratic structure, which makes it difficult to integrate them into functional devices.

“We’ve found a way to control the structure of MOFs and align them in one direction, creating a MOF film,” CSIRO scientist Dr Aaron Thornton, co-author of a new paper published today in Nature Materials said.

“Having the MOFs in alignment means they conduct a current far better, opening up more electrical uses such as implantable medical devices that give real-time information about someone’s health.

“It also gives researchers more control in the development of vaccines, which will fast-track the process.

“MOFs could also be structured in such a way that they’d only react with certain compounds or elements - for example, miners could wear clothes impregnated with a layer of MOFs that tell them when dangerous gases are building up.

“The possibilities are endless.”

Once the hard work was complete the scientists had to prove that the MOFs were in alignment.

This was achieved by placing a polarisable fluorescent molecule in aligned MOFs.

If the MOFs were all in perfect alignment then they would only be able to make them light up along the one axis, in line with the MOFs, so the light could be turned on or off by rotating the film.

CSIRO has already used MOFs to develop a molecular shell to protect and deliver drugs and vaccines, a 'solar sponge' that can capture and release carbon dioxide emissions and plastic material whose strength improves with age.

Print

Print