Study maps origin of sea debris

Australian mathematicians and oceanographers may be able to work out which bits of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch came from where.

Australian mathematicians and oceanographers may be able to work out which bits of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch came from where.

Unpicking the mind-bogglingly complex puzzle has been the goal of new research at UNSW.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch between Hawaii and California is the best-known of several floating piles of garbage, which gather plastic and random debris in giant pools, posing a profound risk to virtually all fish, turtles and birds nearby.

There are at least five enormous garbage patches, each located in the centre of large ocean currents called ‘gyres’, which suck in and trap floating objects.

Researchers Professor Gary Froyland , Robyn Stuart and Dr Erik Van Sebille have created a model that can help determine where the litter came from – a difficult task for a system as complex and massive as the ocean.

“In some cases, you can have a country far away from a garbage patch that’s unexpectedly contributing directly to the patch,” says Professor Froyland.

For example, the ocean debris from Madagascar and Mozambique would most likely flow into the south Atlantic, even though the two countries’ coastlines border the Indian Ocean.

The new model could also help determine how quickly garbage from Australia ends up in the north Pacific, or at what rate one garbage pile leaks into another.

There are a virtually endless array of influences on ocean currents; winds, differences in water temperatures, salinity gradients across the globe, and the forces caused by the spinning Earth all contribute.

But as the currents stir ocean waters, they also serve as barriers to stop mixing between different ocean regions.

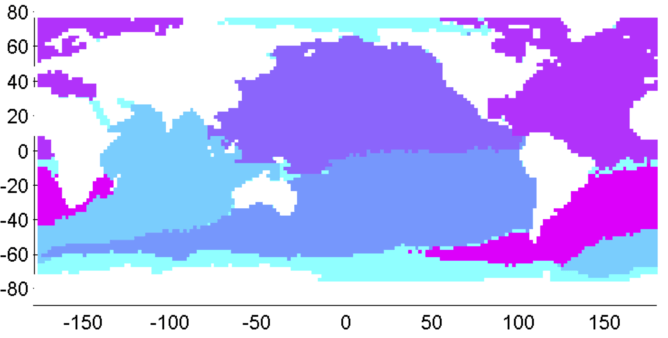

The team simplified their work by dividing the entire Earth’s ocean into seven smaller regions, whose waters mix very little.

Using mathematical methods from a field known as ‘ergodic theory’, their analysis revealed the underlying structure of the ocean without getting bogged down in complex simulations.

“Instead of using a supercomputer to move zillions of water particles around on the ocean surface, we have built a compact network model that captures the essentials of how the different parts of the ocean are connected,” says Professor Froyland.

According to the new model, parts of the Pacific and Indian oceans are actually most closely coupled to the south Atlantic, while another sliver of the Indian Ocean really belongs in the south Pacific.

“The take-home message from our work is that we have redefined the borders of the ocean basins according to how the water moves,” says Dr van Sebille.

The geography of the new basins could yield insights into ocean ecology in addition to helping track ocean debris.

Two of the researchers behind the project have written this article discussing their work.

Print

Print