Turf cooling tested

Experts are investigating the use of water storage systems to help cool artificial grass.

Experts are investigating the use of water storage systems to help cool artificial grass.

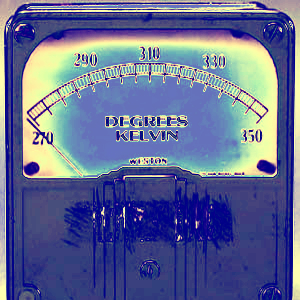

A new study shows that storing water beneath artificial grass can significantly reduce its surface temperature.

Researchers compared self-cooling artificial grass with a water storage and irrigation system to conventional artificial grass, which can reach temperatures up to 70°C on hot days, and yielded some promising results.

On a particularly hot day in June 2020, the cooled turf reached a surface temperature of 37°C, only 1.7°C higher than natural grass. In contrast, conventional artificial turf reached 62.5°C.

The cooling system, according to the research team, offers a safe and cool environment for sports and could also enhance rainwater and flood management by utilising rainwater to fill the system.

Artificial turf equipped with subsurface water storage and capillary irrigation could be a game-changer for urban areas, offering cooler and safer sports courts while assisting in water and flood management.

With urban spaces for outdoor sports becoming scarce, many parks and public sports courts have shifted to artificial turf for its durability under heavy use.

However, this shift comes with challenges, notably the high surface temperatures of artificial turf that can pose health risks.

Researchers in the Netherlands are seeking to address these issues by integrating a subsurface water storage and capillary irrigation system under artificial turf fields.

Dr Marjolein van Huijgevoort, a hydrologist at the KWR Water Research Institute and the study’s lead author, says; “Here we show that including a subsurface water storage and capillary irrigation system in artificial turf fields can lead to significantly lower surface temperatures compared to conventional artificial turf fields. With circular on-site water management below the field, a significant evaporative cooling effect is achieved.”

The innovative artificial turf system features an open water storage layer directly beneath the turf and shockpad, where rainwater is collected and stored.

This stored water is transported back to the turf surface via capillary action, where it evaporates, providing cooling.

“The process of evaporative cooling and capillary rise is controlled by natural processes and weather conditions, so water only evaporates when there is demand for cooling,” explained van Huijgevoort.

Conventional artificial turf can reach surface temperatures high enough to cause burn injuries and heat-related illnesses.

The field experiment in Amsterdam demonstrated that replacing conventional turf with the self-cooling variant resulted in significant temperature drops, achieving a surface temperature close to that of natural grass.

The study also found that air temperatures 75cm above the cooled plots were lower compared to conventional artificial turf fields, especially at night.

“This is a first indication that the cooled plots contribute less to the urban heat island effect,” said van Huijgevoort.

The cooling turf combines the durability of artificial turf with the cooling benefits of natural grass. It also has a rainwater retention capacity similar to natural grass, reducing stormwater drainage and helping mitigate urban flooding. During dry periods, additional water can be manually added to the system.

While the installation costs for this cooling turf can be up to twice as expensive as conventional artificial turf, the researchers recommend a full-scale cost-benefit analysis to assess the true value of the investment.

Further research is also needed to understand how this system impacts surrounding areas and how it performs in different climates with varying storage sizes, materials, and infills.

Print

Print