WA study sees life lost

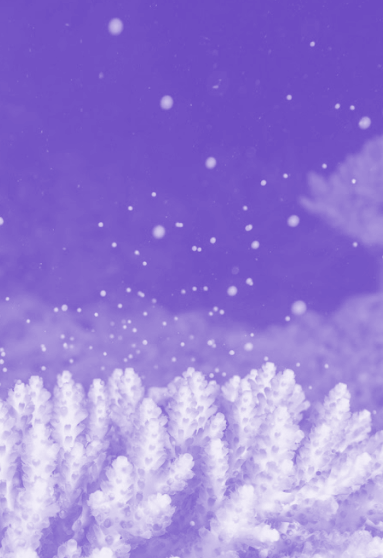

A monumental loss of fish and coral life has been observed at a popular area of Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia’s Gascoyne region.

A monumental loss of fish and coral life has been observed at a popular area of Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia’s Gascoyne region.

Despite the concerning state of affairs, Curtin University research into the event shows there is hope it will recover.

In March 2022, during the annual coral spawning event, calm weather and limited tidal movement combined to trap the coral’s eggs within Bills Bay, at the town of Coral Bay.

This led to an excess of nutrients in the water which consumed more oxygen than usual — causing massive numbers of fish and corals to die from asphyxiation.

Associate Professor Zoe Richards says a lack of oxygen is a well-known risk for tropical coral reefs.

“Severely low oxygen levels in the ocean can create ‘dead zones’ where almost nothing can live, causing a lot of harm to nature and, in tourist areas such as Coral Bay, this can also impact the economy and community,” Associate Professor Richards said.

With help from former third-year undergraduate students and study co-authors Lewis Haines, Sophie Preston, Troy Matthews, Anthony Terriaca, Ethan Black, Yvette Lewis, Josh Mannolini, Patrick Dean and Vincent Middleton, Associate Professor Richards surveyed the area before and after the spawning event.

The team found the level of live coral cover in Bills Bay dropped from about 70 per cent in 2021 to around 1 per cent in 2022, while over the same period the cover of turf algae surged from 27 per cent to 79 per cent.

Importantly, 3,452 healthy corals relating to 26 different genera were recorded at the nine survey sites in the bay in 2018, but after the deoxygenation event only 153 individuals relating to four types of coral remained.

“Some types of corals which used to dominate the area are now gone,” Associate Professor Richards said.

“However, a few hardy corals remain - and now we need to try and figure out why they were able to survive.”

Associate Professor Richards said despite the significant loss of sea life, all was not lost for the area or the people who enjoy it.

“It’s important to note the die-off was localised, meaning there are still healthy corals nearby to seed and help in the recovery of damaged areas,” Associate Professor Richards said.

“This type of deoxygenation event has taken place at Coral Bay before - most notably in 1989 - and the community fully recovered.”

The full study has been published in the Journal of Coral Reefs.

Print

Print